[smbtoolbar]

Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) is a diagnosis that has gained attention since I graduated from physical therapy school. It was not covered in my curriculum. So I feel like I am playing catchup and thought some of you might like to go along!

DCD is a motor disorder that is characterized by either delayed development of motor skills or difficulty coordinating movement. This disorder must not have a medical or neurologic condition that can explain the delay or coordination difficulty. 5-6% of school-aged children have this chronic condition. DCD is more prevalent with boys than girls. This makes me wonder how many of students with DCD in our schools go undiagnosed? What categories of educational disability might be most likely to include students with DCD; maybe OHI? or maybe completely unidentified and under the radar?

Challenges Addressing DCD

This paper summarized several challenges to accessing services and supports for Developmental Coordination Disorder:

- lack of recognition of DCD

- long wait times for services

- relatively high prevalence of DCD

- mandates for many rehabilitation centers do not include DCD

The authors also make the excellent point that even if awareness of DCD is improved, then wait times would also increase. Further, they assert that services for DCD are primarily limited, one-on-one interventions focused on motor impairments while another critical aspect of needed intervention, translating knowledge to and building capacity in other caregivers and other adults, is not addressed. It is this strategy in DCD management that promotes not only skill acquisition, successful long-term function and participation (p413).

The article then describes a school-based service delivery model for occupational therapy: Partnering for Change (P4C) (Missiuna, 2012). This is a tiered approach with an emphasis on partnerships and capacity building between therapists, educators and parents. I found it odd that they did not continue with this model and expand it to the community providers. But the authors stated that service delivery varied too much across practice settings to ‘readily’ apply (p413).

The Apollo Service Delivery Model

The authors felt that the Apollo service delivery model was a better fit and adapted it for managing children with Developmental Coordination Disorder. This model employed 3 levels of intervention: community, group and individual with the primary goal of using population-based interventions to building capacity across all the child’s environments. Examples of population-based interventions include:

- increasing awareness of DCD,

- integrating the child’s and family’s perspective into assessment and intervention,

- improving coordination of services,

- implementing clear graduated paths for services and interventions

- services and interventions focused on function, participation and prevention of with secondary impacts.

These aspects of this approach are aligned with a recent scoping review (Camden, 2015) that identified best practice principles for DCD. The Apollo approach has been implemented previously generally with children with disabilities, but not for a specific diagnosis. This was a wide reaching program that was based out of a rehabilitation center in Southern Quebec and funded after lobbying provincial and regional levels of the Health Ministry and partnering with a provincial DCD parent association.

Collaboration and Funding

Community-based groups were offered as well as individual interventions. Parents and therapists collaborated to focus the community groups on adapted leisure activities (e.g. skiing – it is Canada!, karate and swimming). Research grants from the DCD parent association and local school board funded efforts to increase teachers’ knowledge and skill to manage children with DCD during the school day. Seven schools sent nine educators (each) to six half-day sessions on DCD. Those teachers in turn identified students with potential DCD and invited those students’ parents to a one-day workshop on DCD. This was a huge, collaborative effort; I cannot imagine how many meetings they had to conduct! It also produced highly satisfied parents, teachers and health professionals. Additionally, they identified some persistent challenges:

- few criteria to guide decisions about individual services

- groups were time-consuming and difficult to sustain

- school education sessions needed better integration with other services (p415)

This effort was comprehensive across practice settings and included program evaluation and continuous quality improvement.

Lessons Learned

Here are the ‘lessons learned’ as delineated by the authors:

- partner with parents and parent associations for redesign services

- build capacity and partner with educators, physicians and community groups

- select or develop a service delivery model that follows best practice principles for DCD

- offer graded services and specialized services only when needed (pp420-22)

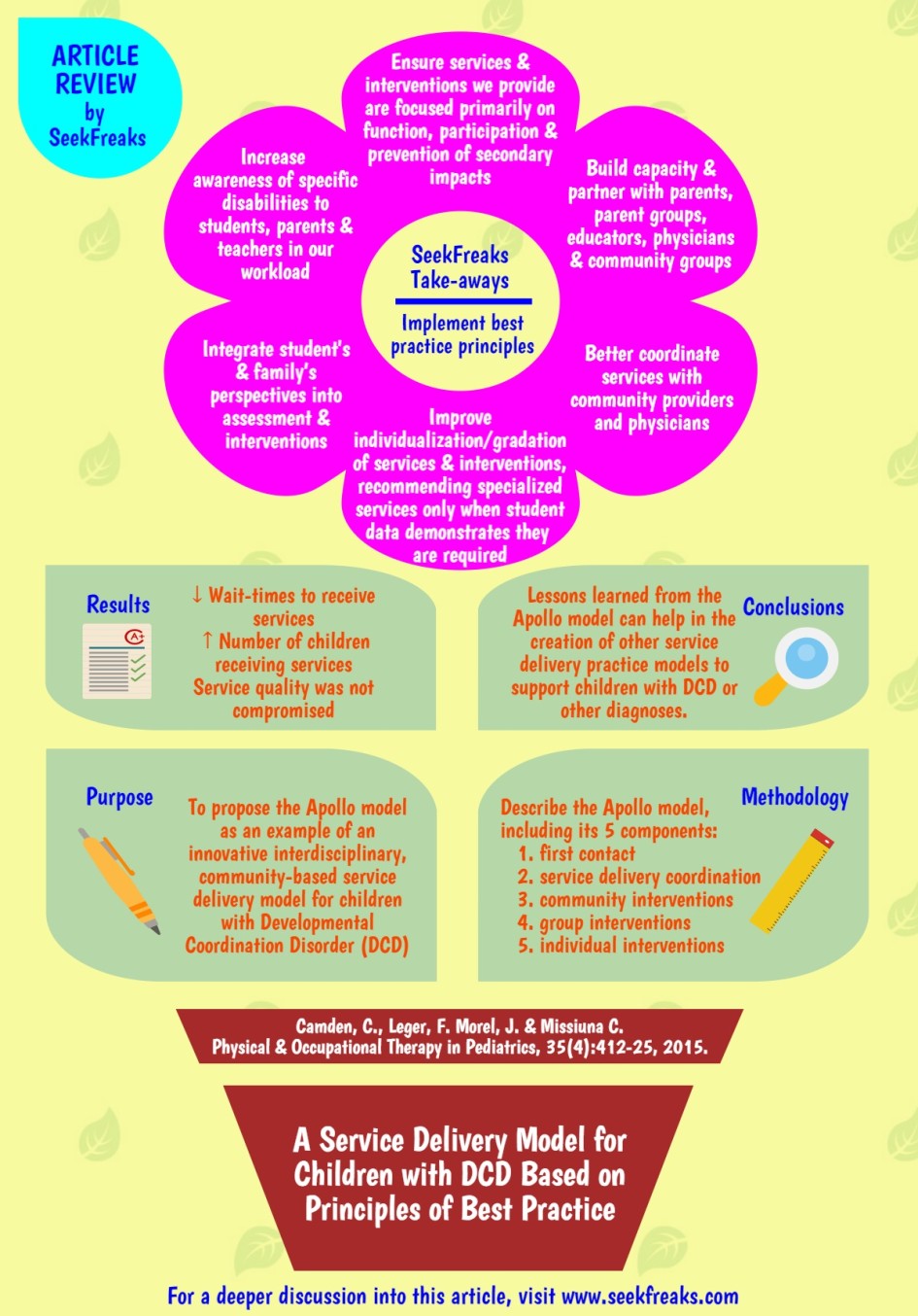

SeekFreaks Take-aways

While impressive and successful, I find it daunting to think of how to begin such an effort in my schools. We all know from experience that it takes a team…but to get big results, it takes many people giving big efforts. I think these learned lessons may be applied on a smaller scale and with a variety of diagnoses. Here are some suggestions to consider for our practice:

- increase awareness of specific disabilities to the students, parents and teachers in our workload

- integrate our students’ and family’s perspectives into assessment and interventions

- better coordinate services with community providers and physicians or at least improve (or initiate) communication

- improve individualization/gradation of services and interventions we provide, recommending specialized services only when student data demonstrates they are required

- ensure services and interventions we provide are focused primarily on function, participation and prevention of secondary impacts.

- build capacity and partner with parents, parent groups, educators, physicians and community groups

- attend and implement best practice principles (the PT COUNTS research confirms we know best practices but we don’t employ them in our daily practice!)

Can we do it? Select one or two of these recommendations to focus on. Make small sustainable changes. The longest trip begins with one step.

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

Readers of this article also read:

Article Spotlight: Top 10 Lessons from EACD’s Guideline for DCD

5 Practical Tips for Classroom Arrangement

Article Review: Can Online Modules Improve the Practice of Therapists?

Motoropoly 1: Motor Learning Principles in School – Instructions, Feedback & Demonstrations