[smbtoolbar]

Quantitative studies are often seen as scientific and unbiased, but have also been criticized for being controlling and limited, forcing behaviors into specific quantifiable categories. On the other hand, qualitative studies “capture life as it is lived”, but has been criticized as being unscientific and prone to bias (Abusabha and Woelfel, 2003).

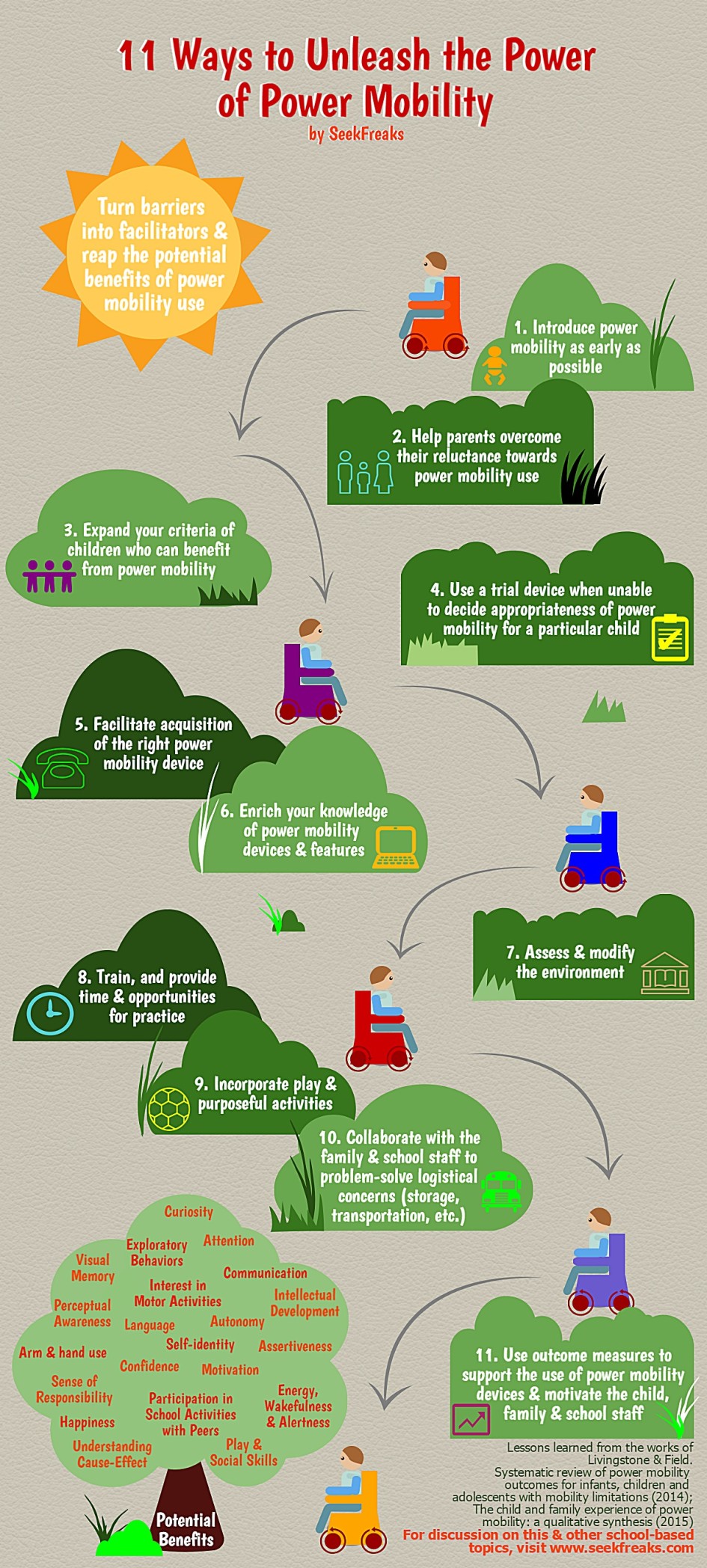

At SeekFreaks, we consider both types of studies as essential and complementary. While quantitative studies provide measurable results of an intervention, qualitative studies are able to add the subjects’ perspectives and interpretations of their own experiences. Luckily, I found 2 systematic reviews (SRs) on the topic of power mobility for children, a quantitative review and a qualitative review. I thought this would be a great time for our 1st SeekFreaks research article face-off! Based on the lessons learned from these and other related studies, we also created the “11 Ways to Unleash the Power of Power Mobility.”

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

DUAL ARTICLE REVIEW

Both studies were written by the same authors, Livingstone and Field. They first sought out quantitative support for use of power mobility (the quantitative SR was published first, in 2014; the qualitative study was published in 2015). Many studies on children’s use of power mobility was excluded from the 1st study because they were qualitative in nature. The authors felt that it was thereby warranted to conduct a SR of qualitative studies to analyze the children and family’s perspectives on power mobility use.

Twenty-nine studies were included in the quantitative SR, while 21 were included in the qualitative SR. Nine studies were included in both SRs, since these studies have quantitative and qualitative components.

Findings

From the Quantitative SR

The quantitative SR conceded that based on the levels of evidence and structure of the included studies:

- the overall body of evidence is more descriptive than experimental, and

- outcomes research on power mobility usage is still in its infancy

The following are the clinical messages from this study:

- One study has a high level of evidence (Level II). Results from this randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated positive impact on overall development & independent mobility

- Evidence primarily from observational studies suggests:

- On body function & structure: + impact on overall development

- On activity: + impact on on power mobility skill development

- On participation: fewer studies & lower quality evidence support + impact on participation

- Environmental factors appear to influence power mobility use & skill development

From the Qualitative SR

The qualitative SR findings can be summarized under 3 overarching themes:

- Power mobility experience promotes developmental change and independent mobility

- Power mobility enhances social relationships and engagement in meaningful life experiences

- Power mobility access & use is influenced by factors in physical, social and attitudinal environment

The qualitative SR discussed further how these results are consistent with, and enriches those reported in quantitative studies.

Benefits of Power Mobility

The SRs elucidated on the multiple positive effects of power mobility usage. We attempt to highlight some of the benefits that are most meaningful to the students’ schooling:

Academics

The authors found that power mobility may facilitate:

- Curiosity

- Attention

- Self-initiated communication

- Language development

- Intellectual development

- Visual memory

- Perceptual awareness

- Participation in school activity with peers

- Play & social skills

- Understanding of cause-effect

- Energy, wakefulness and alertness

- Arm and hand use

- Exploratory behaviors

Attitude

Power mobility may have positive effects on the student’s self-image and behavior, such as enhanced:

- Autonomy

- Self-identity

- Confidence

- Assertiveness

- Motivation

- Sense of responsibility

- Happiness

- Interest in motor activities

Facilitator or Barrier?

The SRs reported that certain factors may serve as either facilitators or barriers to power mobility use. These include: the clinicians’ attitudes, the social environment, the features of the power mobility device and the physical environment. By turning these barriers into facilitators, the student can reap the potential benefits of power mobility use.

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

11 WAYS TO UNLEASH THE POWER OF POWER MOBILITY

1. Introduce power mobility as early as possible

- The study reported that a child who use power mobility sees the device as a part of him/herself. The sooner power mobility is introduced, the sooner it becomes part of their natural repertoire, just as walking becomes natural to a child with typical development.

- Movement facilitates learning. Conversely, limited movement can limit learning. Lynch et al (2009) described power mobility use of a 7-month old infant, and how it improved the child’s cognition and language. So, SeekFreaks, if you are working with a child at risk of immobility, no matter what age, what else are you waiting for?

2. Help parents overcome their reluctance towards power mobility use

- The article found that parents’ attitudes changed from reluctance to acceptance when they saw their children move freely with power mobility. So if we can at least convince parent/guardians to try out power mobility for their child, the use of the device itself may do the rest of the persuasion to full adoption of power mobility.

- It is important to note that for many children the use of power mobility does not necessarily preclude other means of mobility, such as walking. It simply provides them with an immediate means of mobility while they develop walking skills and/or it provides the child multiple options for mobility (e.g., walking with support within the house or the classroom, and power mobility for longer distances). The quantitative SR even points out that power mobility may stimulate interest in motor activities.

- You may also want to highlight that power mobility is also good for caregivers: the SRs reported that it decreases the reliance on caregivers and the physical demands of providing care.

3. Expand your criteria for children who can benefit from power mobility

- Clinicians can hinder access to power mobility by excluding younger children and children with cognitive and upper arm limitations as likely candidates.

- The article points out that cognition has often been used by clinicians to determine “readiness” for power mobility. However, if power mobility enhances cognitive development, are we then excluding candidates whose cognitive readiness for the device can develop with its use?

4. Use a trial device when unable to decide appropriateness of power mobility for a particular child

- Contact vendors to try out different features that can help the child overcome their disability to control and maneuver the device.

- Monitor the progress to see if the child is building readiness to have his/her own device.

- Use before and after videos to demonstrate child’s acquisition of power mobility skills, motivation, and increased independence.

5. Facilitate acquisition of the right power mobility device

- Depending on the policies of your school district, securing a wheelchair may or may not be your responsibility. Either way, you can still facilitate the acquisition of one.

- Help parents negotiate the insurance and medical requirements to acquire a device.

- If the family is working with a wheelchair clinic, work closely with them. Describe how the child will be utilizing the mobility device in school.

- Consider the family and the child’s lifestyle. How and where would they like to use power mobility?

- Cite studies in your letters of medical necessity like these 2 SRs to show how the power mobility device can address the child’s specific needs.

- Refer to our article on the 4Cs of LMNs (Letters of Medical Necessity).

6. Enrich your knowledge of power mobility devices and features

- Better your skills in determining the right fit for the child.

- Learn which features work best in different environments, including those that the student will deal with in the school, such as the hallways, school yard, elevator, ramps, field trips, etc.

- Attend assistive technology conferences to see the latest equipment.

- Network with wheelchair vendors and use them as your resources.

7. Assess and modify the environment

- Survey the classroom, hallways, playground, gym, lunchroom and other pertinent areas for access

- Offer suggestions on how modification of the classroom layout, home layout and school environment can facilitate successful use of the device.

- Assess bathroom(s) that the child can use while in school. Work with the school administrators and custodians to improve access getting through the door, in & out of the stall & under the sink.

- Problem-solve with the student the best routes to use when outside the school

8. Train, and provide time & opportunities for practice

- Be patient and provide ample time for practice. The qualitative SR described how children use self-directed learning when mastering power mobility devices. This requires time to learn from trial-and-error.

- Practice in different environments: ramps, outdoors, complex terrains or in various weather conditions.

- Consider creating well-thought-out barriers to provide opportunities to practice certain skills during the school day. Would a few feasibly negotiable obstacles within the classroom or at home help the child hone his/her maneuvering skills?

- Teach self-advocacy skills so the student can seek assistance from others independently

9. Incorporate play and purposeful activities

- The quantitative SR reported varied results in impacting interaction with others (i.e., getting a power mobility device does not necessarily mean the child will start socializing and participating with their peers)

- Added support may be needed from the therapist to design practice opportunities that incorporate socialization and dynamic interaction with peers. Play and purposeful school/classroom activities are perfect opportunities to enhance power mobility skills and socialization at the same time!

10. Collaborate with the parents and school staff to problem-solve logistical concerns

- Educate the child, family & school staff on safe use of certain adaptations such as bus lifts and ramps.

- Work with school administrators to ensure inclusion of student on field trips.

- Problem-solve with the family and school staff the storage of, and transportation with power mobility devices. (The articles pointed out that these are big concerns for power mobility device ownership.)

- Connect the family with community-based resources who can assist the family in planning wheelchair-friendly transportation, securing wheelchair-friendly homes, and arranging wheelchair-friendly leisure activities.

11. Use outcome measures to support the use of power mobility devices

- Seeing progress can be motivating to the child, family and school staff.

- Use various outcome measures that can demonstrate proficiency in use of device, improvements in body structure & function (e.g, vital signs), and impact in the student’s participation level.

- Measuring participation for power mobility users remain a challenge. Field et al (2015) found potential tools, but concluded that none were best suited for the purpose.I recommend choosing a meaningful participation task with the student and creating your own way of measuring progress (e.g., amount of time playing with peers in the playground; support and cues needed to get on and off the bus lift; number of occasions child joined the family during weekend activities such as grocery shopping, going to the park).

- Create a graph or chart that students can fill in so they can monitor their own progress.

- Finally, Livingstone and Field voiced the need for more participation outcomes in research. We encourage you to help enrich our practice by creating your own tools and/or sharing your outcomes.

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

Conclusion

Livingstone and Field’s systematic reviews provide support for use of power mobility devices. The quantitative SR made it clear that there is much needed research for quantifiable outcomes. For this very reason, the authors’ decision to conduct a 2nd SR on qualitative studies was wise, and helped enrich the findings of the 1st. It provided great insight into the child and family’s perspectives on power mobility. As school-based therapists we should strive to transform barriers into facilitators so that the student can reap the benefits of power mobility use.

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

Other resources you can look into:

- Practice consideration for introduction and use of power mobility for children. Livingstone & Paleg (2014). Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology.

- Modified ride-on toy cars for early power mobility: a technical report. Huang and Galloway (2012). Pediatric Physical Therapy.

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

Seeking Your Views

Share your successes and challenges promoting the use of power mobility devices.

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

Readers of this article also read:

Functional Classification Systems for Children with CP

The 4 Cs of Letters of Medical Necessity that Gets Equipment Funded

7 Wheelchair Operation Tests for School-based Therapists

Late Summer Reading List for Seasoned School-based OTs, PTs and SLPs

February 2, 2020 at 4:12 pm

Beautiful graphic interpretation and summary !