Written by Carlo Vialu, PT, MBA, co-creator of SeekFreaks. He loves promoting function and participation for children and youth with disabilities, from our assessment to our interventions, via his continuing education courses: The Well-Equipped Therapist! School-based OT & PT Symposiums, Everything’s Measurable, and the live online Experts Series. Read more about these courses after the article.

[smbtoolbar]

Imagine somebody tied both of your hands behind your back and asked you to provide therapeutic interventions. Can you still effect change? Are you still an occupational therapist or a physical therapist? While this study tried to answer the first question, it inadvertently also answered the latter.

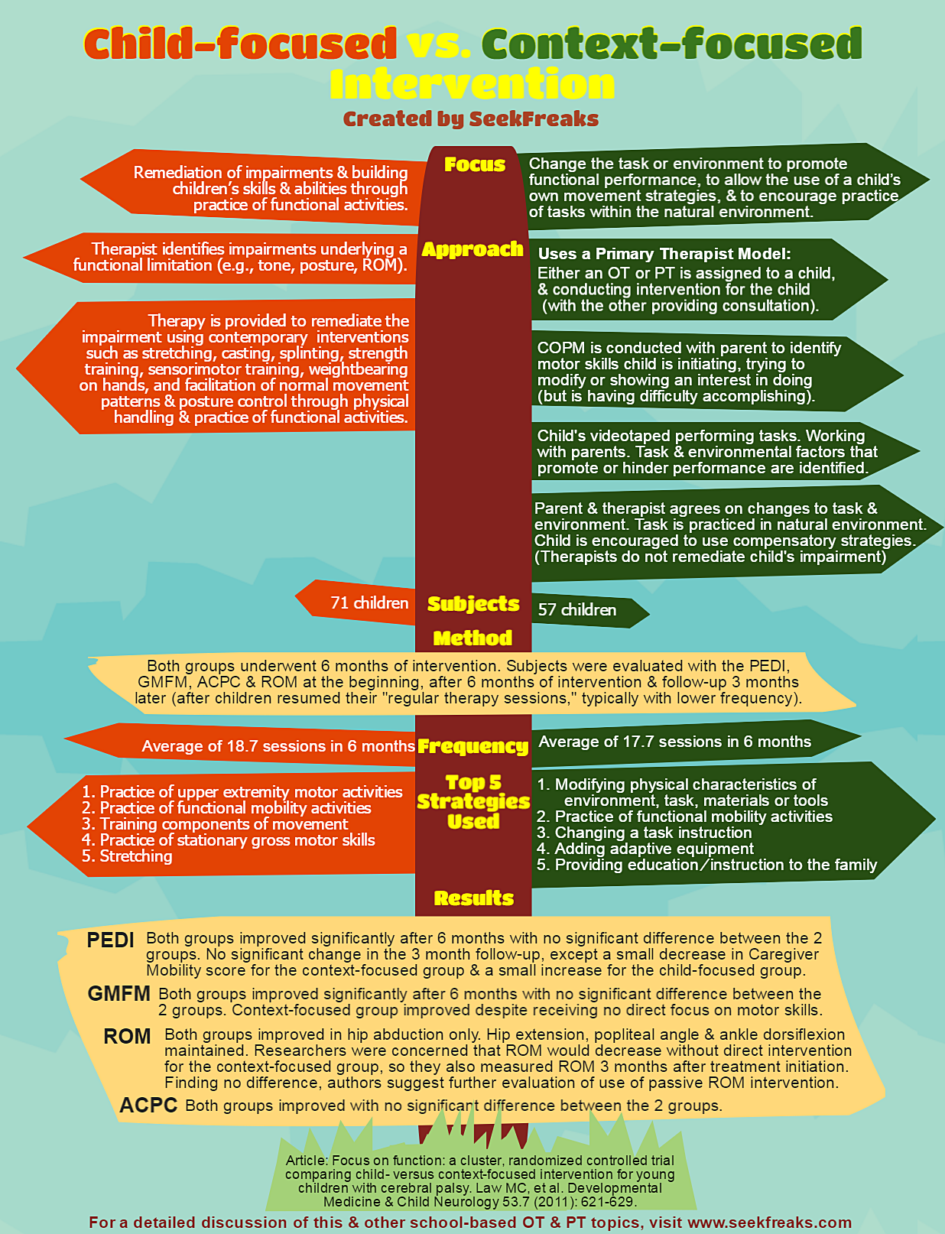

The Context-focused Approach

In an accompanying article, Darrah et al (2011) described a novel treatment approach “that focuses on changing factors in the task and environment rather than on remediating a child’s motor impairment.” You may be thinking, “That’s not so novel; I do that all the time.” It was novel because it was prescriptive: remediation of impairments is not permitted at all! In addition, it encourages therapists to build on the child’s current movement strategy (even those traditionally thought of as atypical), and discourages the use of hierarchical preference of movement solutions.

The “context-focused approach” as it came to be known uses a primary therapist model, where only one therapist, either an OT or a PT, conducts assessments and interventions for the child, while the other provide consultation to the primary therapist to problem-solve issues within his/her expertise. While we encourage you to read the full article for a thorough description of this approach, we summarized the general steps below:

- Identifying the tasks the child is ready to learn: This is accomplished by conducting the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) with the parent to identify motor skills that the child is initiating, trying to modify or showing an interest in performing, but is having difficulty accomplishing.

- Videotaping: The child is videotaped performing the tasks identified in #1

- Task analysis: The therapist and the parent observe the child and watch the video, identifying task and environmental factors that promote or hinder performance.

- Intervention planning: Parent and therapist agrees on task and environmental modifications.

- Practice: Task is practiced in the natural environment with agreed-upon modifications. Initially, therapist works intensely with the child and family to find the best strategy via trial and error. The family is then left alone to “experiment” and “provide the child with practice time.”

- Monitoring: Therapists expect quick success. Using a “fail quickly” approach, strategies that are ineffective after 2 weeks of trial are re-evaluated.

The investigators found that therapists in their pilot study still preferred to use remediation over task and environmental modification. So they became more prescriptive in not allowing therapists to use any remediation strategy.

Darrah et al (2011) provided some examples of interventions in pre-kindergarten students. A child learning to balance himself on the toilet seat was asked to sit from the side so he can hold on to the sink for support. Another child became successful picking up cereals to feed himself in one session by spreading peanut butter on his fingertips (with the assumption that peanut butter will not be necessary in the future when he develops a pincer grasp).

Time to Test it Out

With the context-focused approach defined, Law, et al (2011) set out to test its efficacy against a child-focused approach (the child-focused approach utilized strategies to remediate impairments underlying a functional limitation). Subjects were divided into 2 groups and received either approaches for 6 months: 71 subjects for the child-focused group and 57 for the context-focused group. All children were diagnosed with cerebral palsy, classified across different Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) Levels, from I to V. The children were 12 months old to 5 years 11 months old.

Students were tested prior to start of the intervention, after the 6-month intervention period, and 3 months after the end of the interventions (during which time the subjects returned to their usual intervention). Measures utilized include: Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI), Gross Motor Functional Measure (GMFM), range of motion (ROM) and the Assessment of Preschool Children’s Participation (ACPC).

Findings

Both groups showed significantly improved PEDI, GMFM and ACPC scores after 6 months of intervention. There were no significant differences in the test performance of both groups. No further change was noted at the 9th month testing (after the children resumed their regular therapy sessions), except for the PEDI Caregiver Mobility Scale, where a slight increase was recorded in the child-focused group, while a slight decrease was recorded in the context-focused group. Both groups exhibited maintenance of range of motion for hip extension, popliteal angle and ankle dorsiflexion, and an increase for hip abduction.

The top 5 strategies used by the therapists applying the child-focused approach in the study were:

- Practice of upper extremity motor activities

- Practice of functional mobility activities

- Training components of movement

- Practice of stationary gross motor skills

- Stretching

On the other hand, the top 5 strategies for therapists applying the context-focused approach were:

- Modifying physical characteristics of environment, task, materials or tools

- Practice of functional mobility activities

- Changing a task instruction

- Adding adaptive equipment

- Providing education/instruction to the family

Comparing the 2 approaches, they share only 1 common strategy among their Top 5s – the practice of functional mobility activities. On average, the child-focused subjects received 18.7 sessions in 6 months, while the context-focused subjects received 17.7 sessions in 6 months.

Now the good news, bad news.

Good news! That there was generally no decline at the 9th month testing means that the children retained the skills they have learned – one sign that motor learning occurred. Bad news is that there was generally no improvement despite the children receiving their “usual therapy” during this time – which puts into question the usual therapy they were receiving. The study points out inconclusively that this may be due to the general decrease in frequency of services (inconclusively because different studies have reported different results with regards to frequency – so I guess, the resolution regarding optimal dosage will have to wait). Are there other reasons at play, such as the type and manner of intervention they received?

SeekFreaks Take-aways

Here are some interesting results and lessons from this study:

- The context-focused approach is as effective as the child-focused approach.

Though no doubt an interesting result, it makes sense if you look at it from the motor learning perspective. Motor learning can occur by modifying the task and the environment to encourage the child to practice the task repeatedly, utilizing strategies that the child’s body affords him.

- Passive stretching may not be necessary to maintain range of motion.

Since remediation strategies such as stretching is not allowed under the context-focused approach, the investigators were concerned that range of motion (ROM) will be lost. Thus, in addition to the pre- and post-tests, ROM was also measured 3 months into the intervention. The results, therefore put into question not just this concern, but also the utility of stretching. It supports the findings of Owen et al (2011) and Katalinic et al (2010) that regular stretching did not produce clinically important changes in joint mobility. So, is it time for therapists to stop stretching?

This result may also support the idea that there are other ways to maintain range of motion, such as through active movement when completing functional activities.

- GMFM may improve without direct focus on motor skills.

The investigators surmised that “the ability to improve functional skills and practice them more often contributed to the changes in their motor abilities.” Perhaps, this may mean that being prescriptive on how to perform an activity may not be necessary in improving motor skills. We can set up the task and environment to provide frequent opportunities for practice, and encourage students to utilize strategies that their body allows. (Do you have a better stipulation on why this happened? Share below.)

- Families can be involved from assessment to intervention.

We all know that the family can be a great resource in getting to know the child. This study further supports that they can also be our partners in assessment, goal setting, intervention planning and intervention implementation. Partner up with families and empower them to help their children improve!

In school-based practice, I would extend this lesson to teachers and other school staff. Like families, they spend the most time with our students in schools. So, similarly, we should partner with them when assessing the student, setting goals, planning interventions and implementing them.

- Both groups of therapists have embraced practice of functional mobility activities.

For the sake of the study, the researchers had to be strict, and instructed therapists to either provide remediation alone, or task and environmental modification without remediation. It was great news to hear that despite this limitation, both groups still chose to practice functional mobility activities. If there has been a preponderance in evidence for our practice, it is that an activity-focused approach is essential in learning motor skills.

- The primary therapist model is feasible, and can be just as effective.

The researchers noted that one of the advantages of the primary therapist model is having a primary contact. Therefore, families “do not have to filter and manage intervention ideas from many resources.”

- We are still therapists even if somebody tied our hands behind our backs!

Hooray! It might actually be the use of our cognitive skills (i.e., clinical reasoning, task analysis, problem-solving and other relevant skills) that makes us effective…and therefore, worthy of the title “occupational therapist” or “physical therapist.” Shake off the need to be hands-on all the time. “Brains on” can also be just as effective.

Final Thoughts

So, is one approach better than the other? Two cliches come to mind: “everything in moderation, including moderation itself” and “there is a time for everything and everything in its time.” Each intervention approach has its own merits – a statement which we think is supported by this study. As therapists, we should discern when one is needed more than the other. However, what Darrah, et al (2011) showed us is that therapists love gravitating towards focusing on the child, and do not take enough advantage of focusing on the context. We should strive to achieve the right proportion of each that is needed depending on the situation.

This lesson is most useful for all us in school-based practice, where a therapist’s “hands on” time may be limited. We should partner with parents/guardians, teachers and other school staff. Together, we can conduct ecological assessments, create goals and plan interventions, modify the school task and environment, try out strategies to find ones that create success quickly, and encourage practice of the skills in the natural environment.

Join Carlo Vialu and other experts at these all evidence-based, all practical continuing education online courses:

1 Pingback