[smbtoolbar]

Happy Physical Therapy Month to All!

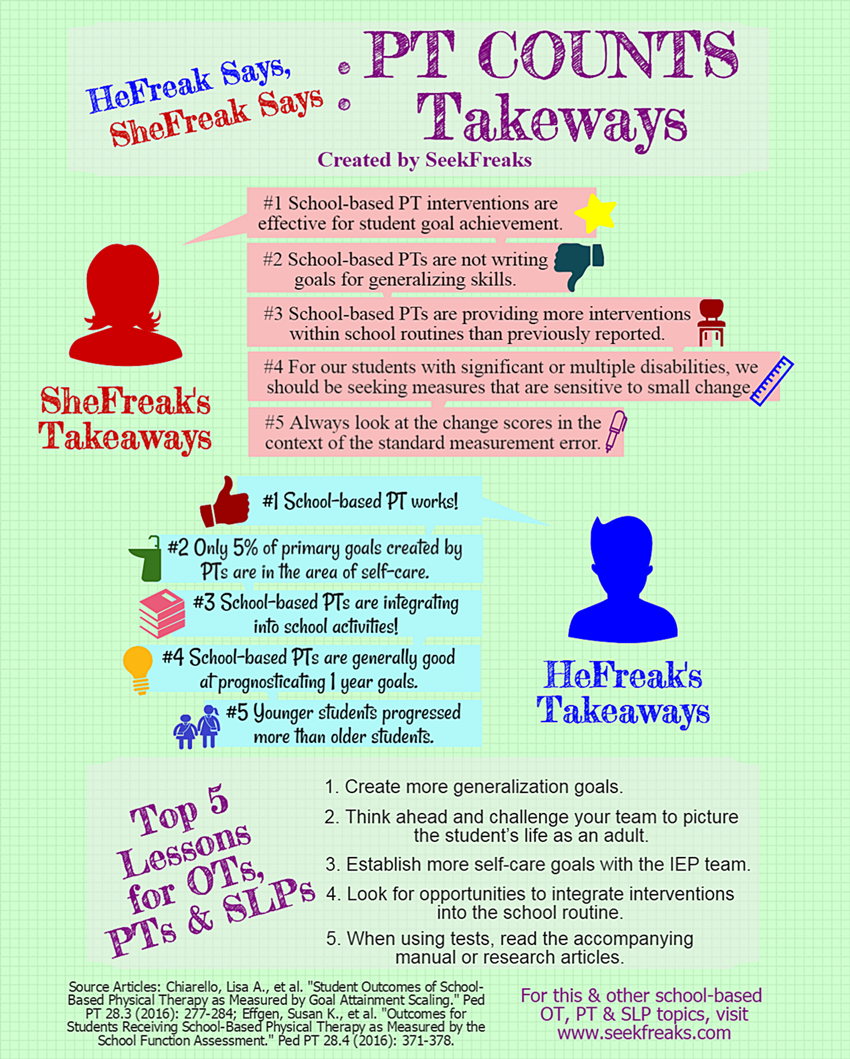

We celebrate PT Month with our first HeFreak Says, SheFreak Says article. We have been talking about creating one in the past year. Then came the first publications from the PT Related Child Outcomes in the Schools (PT COUNTS) study (Chiarello et al, 2016 and Effgen et al, 2016); which we think give a great opportunity for each of us to come up with our own Top Takeaways and start a dialogue.

So how does this work? Separately, we each came up with our Top 5 Takeaways (which would explain 2 overlaps), providing commentary and application for each. Then we exchanged notes and provided our takes on each other’s takeaways and commentaries. We hope this inspires all of you SeekFreaks out there to add your comments and/or insights!

Although the study is focused on PT, we intentionally made this article beneficial to OTs and SLPs, as well. We summarize the article with our combined Top 5 Lessons for school-based OTs, PTs and SLPs.

We start with what SheFreak says.

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

SheFreak’s Top 5 Takeways

This research is very welcome as it directly examines student outcomes at school. This is the primary way physical therapists demonstrate their expertise and value to the IEP team. It also provides direct evidence to inform school-based practice!

SheFreak’s 1st Takeaway: School-based PT interventions are effective for student goal achievement.

The GMFCS level of the student and diagnoses had NO effect on the student’s goal attainment!! Does this mean we are effective across varied levels of involvement or are we writing individualized goals well or are we not setting the goals high enough? This can mean many things…

Application:

- Mostly celebrate!

- Impact of interventions is not driven by mild impairment or certain diagnosis

- While earlier intervention (elementary) appears most beneficial, it would be an error to interpret this to mean intervention later in school (middle/high school) cannot be powerful and critical.

HeFreak says: I expected that we would both champion this point…it is PT month after all, so why not celebrate! I’m glad you picked out the finding that the GMFCS level and diagnoses of the students in the study had no effect on goal attainment. This may mean that the PTs are able to take into consideration student’s strengths and needs in creating realistic goals. Kudos to the participants in utilizing Goal Attainment Scales effectively! I call for more use of Goal Attainment Scales in our practice.

SheFreak’s 2nd Takeaway: School-based PTs are not writing goals for generalizing skills.

Why not? If the skills is not generalized or mastered in various settings, the expertise of a school-based therapist is still needed! Are we delegating this critical point to educational staff?

Application:

- Examine the focus of our goals overall. Is there variety according to student need-emerging skill, skill mastery/consistency or generalization

- Are we too reliant on consultation and missing a more effective path through direct intervention? Review your workload, do you need to more actively advocate for exit? Are there students whose rate of progress would increase with direct intervention? How effective is consultation for goal achievement?

HeFreak says: I am actually curious to know how the authors would have classified a student’s GAS as generalization. Gordon and Magill in Physical Therapy for Children by Campbell, et al (2011) describes generalization as the transfer of learning from the “clinic” into the client’s everyday world. For example, being able to transfer from the wheelchair to a commode in a new restroom during a class trip or an unfamiliar restroom within the same school, after much practice using a familiar restroom close to the classroom. This sounds like a great +1 or +2 goal (greater than expected outcome and much greater than expected outcome, respectively). For a child with great potential for improvement, It can even be your 0 (expected outcome). Try it out next time you use GAS.

Picking up on SheFreak’s question about delegating, we need to discern when to provide direct intervention, and when to delegate. When providing direct intervention, introduce variety by practicing in different environment (variety helps transfers of skills as discussed in the SeekFreaks article on motor learning: Motoropoly – Part 2).

When delegating, be intentional. The great thing is that teachers and classroom staff are with the student for most of the school day, so they can be there when natural opportunities occur to practice a skill. As Gordon and Magill (referenced above) stated generalization “would occur when all the characteristics of everyday living environment are included in the intervention strategies, wherever they take place.”

When delegating, school-based therapists should educate and troubleshoot with teachers and classroom staff how to elicit practice of the same skill in different contexts (such as the example of toileting above). Encourage them to not just provide support to the student during novel situations, but also to ask the student questions so that he/she can develop problem solving skills.

SheFreak’s 3rd Takeaway: School-based PTs are providing more interventions within school routines than previously reported.

Therapists reported that for 61% of the students, performance of the primary goal behavior was addressed and measured within a school activity or routine. Hooray!! I hope this means we have moved the needle on improving individualization of interventions and decreased our reliance on the pull-out model.

This is not in agreement with previous reports of school-based PT interventions. Could this be due to the sampling of this study? School-based PTs were recruited from the APTA, Section on Pediatrics and volunteered to participate in PT COUNTS. Might their practice not be representative of typical school-based practice?

Application:

- Examine your workload for type of intervention

- Can you provide the clinical reasoning or data to support how and where you are intervening? Write it out or say it out loud.

HeFreak says: I actually selected this as my 3rd takeaway, so more on my take on this later. Thanks for pointing out that this is an improvement from previous reports. This is progress towards the least restrictive environment, for sure. I like SheFreak’s idea of providing clinical reasoning and data when intervening within the school routine. This way we can explain the intent to a teacher who may be surprised with our presence in the classroom. And the data will help show the effectiveness (or not) of the integrated service we are providing.

SheFreak’s 4th Takeaway: For our students with significant or multiple disabilities, we should be seeking measures that are sensitive to small change.

We struggle to find applicable, valid measures to assess the performance of our most significantly involved students and students with multiple disabilities. Often the progress we make with students with multiple or severe disability is painstakingly slow and small in effect change. Sometimes we are working to prevent the loss of skills or skill use, not trying to teach new skills. What sensitivity is required to discern the tiny progression or incremental impact of intervention with this population?

How can we best rate student progress and intervention effectiveness? While this varies from case to case, as the premise of IDEA is individualization and perhaps our evaluations/assessments should be individualized also to capture small or sub-clinical change.

For the students we intervene with in public schools, what is a reasonable rate of progress? What is the time frame to afford an intervention to show its effects or appropriate rate of change?

Which measure can capture what I am working to change with intervention?

Application:

- Clarify what, exactly, you are trying to assess. Are you trying to describe, delineate, determine delay, inform intervention, offer prognosis?

- Explore the list of pediatric assessments provided by the Academy and SeekFreaks’ collection of tests (for balance, walking and wheelchair operation). Find three assessments that would fit one or some of your needs and TRY them!!

- Look for evidence that would predict time frame for skill acquisition. If you cannot find it for your student’s specific age or diagnosis, try to find some relevant evidence that you can apply even for an estimate.

HeFreak says: Excellent takeaway! I’m always glad when I hear about better tools and guidance for children with more severe disabilities. While they have the most needs, we seem to have the least number of tools to help them succeed.

GAS is more individualized. A therapist can take into account the severity of the student’s disabilities to create realistic, and measurable goals. As mentioned earlier, SFA ratings may be too broad. Effgen et al (2016) pointed out that one of the assessment’s “leap” in rating is from “inconsistent” to “consistent” performance. For students with severe disabilities, consistency may not be a “realistic expectation,” putting a ceiling to the student’s rating.

Should we discontinue using the SFA for students with severe disabilities? I think the SFA is still useful to create a baseline of the student’s ability to function in the school. However, you may need to decrease its use to monitor progress – perhaps to once a year or longer. And make sure to use GAS when creating goals so you can objectively measure the student’s progress. For more ideas and examples in using GAS, read about the APPT’s Fact Sheet on Goal Attainment Scaling, a link of which you can find in our 10 Handy APPT Fact Sheets. Though the fact sheet was created by PTs, they are very usable to OTs and SLPs, as well.

SheFreak’s 5th Takeaway: Always look at the change scores in the context of the standard measurement error.

Attend to the standard deviations in relation to the scoring rubric applied; how close are the? The PT COUNTS sample was primarily students with cerebral palsy. We know how variable this diagnosis presents in functional contexts, in this case, school functional performance. In this study there were large standard deviations, some close to 50% of the SFA criterion score.

Attend to the standard error of measurement which is different for each of the SFA sub-scales.

Application:

- Always look at the numbers provided only within the context of measurement error and standard deviation.

- Examine and evaluate the sample. How was it done? Does it match reality? Does it match the student or population you are applying the results to?

- What is the reported reliability of the tester? Would that impact how you view the results?

HeFreak Says: Great points, SheFreak! This reminds us to always read the manual before using a test. Shorter tests, like the 6-Minute Push Test, do not come with manuals. But they are described in research articles. Read them, and learn not just to master the test, but also how to interpret results. They may have norms, or they may even tell you what change in score, time or distance would signify a minimally clinical important difference. By the way, SeekFreaks compiled some of these tests and their source articles (click here for balance, walking and wheelchair operation tests).

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

HeFreak’s Top 5 Takeaways

HeFreak’s 1st Takeaway: School-based PT works!

Students in the study (n=296) on average slightly exceeded their expected goals as measured by Goal Attainment Scaling. So they did not just meet their goals, but also slightly exceeded them.

Additionally, over 51% of students showed improved participation (beyond estimated measurement errors), using the School Function Assessment (SFA). As you would remember from our discussion of the ICF Domains, participation is the pinnacle of successful interventions.

However, this begs the question about what happened to the 49% whose SFA did not improve? One reason may be that the SFA is not sensitive enough to capture the student’s improvement in participation. The SFA has 6 general ratings for each item under Part I Participation. Although it is a very useful tool to summarize a student’s participation, the 6 ratings may be too broad to demonstrate small improvement.

Another reason may be that we need to increase our focus on participation. Here are some things to consider:

- Check if the goals you wrote have the tell-tale signs of a participation statement as discussed in the article Recognizing ICF Domain Words:

- Does it contain an active word?

- Does it contain 1 or more prepositions followed by people, place or time to indicate with whom, where in the school, or when during the school day the action will occur?

- Embed yourself into the class routine.

- Perform an ecological assessment

- Address the context where the child’s participation occurs, and

- Train the classroom staff to maximize skill practice during real class activities.

SheFreak says: We both took this message home, but got some different points out of it. While I do hate to hear anything against the SFA, this research really forces some hard questions about the sensitivity of the SFA. I also agree that this may be indicating we need to target our interventions and focus more on participation. I think reviewing the student goals we work on for ICF Domain, active words and then our intervention plans or IEP service delivery for a % of where we are intervening. I would take it one step further and see what data we are collecting for progress monitoring (‘how will student progress be monitored…’) and get a % of how many student we collect participation data!

HeFreak’s 2nd Takeaway: Only 5% of primary goals created by PTs are in the area of self-care.

Therapists in the study were asked to identify the primary goal among all the goals a student has. Only 5% of the identified primary goals fall under self-care. Why does this upset me? Because self-care skills are important for our students to become successful productive citizens.

- According to National Longitudinal Transition Study – 2, which followed a “nationally representative sample of secondary school students with disabilities who were 13 to 16 years old” for 10 years. The researchers noted that 8 years after high school, 59% of young adults in the general population lived independently, compared to 45% of the young adults with disabilities. Is lack of self-care skills one of the reasons? Look at the studies below:

- Test, et al (2009) in a systematic review of transition literature found that independent self-care skills in youth with disabilities has a moderate level of evidence as predictor of independent living, and potential level of evidence as predictor of post-secondary education and employment. So in addition to just predicting independent living post-school, independent self-care skills may also predict employment and post-secondary schooling.

- In fact, Carter, et al (2012) found that independence in self-care is one of the predictors of post-school employment for students with severe disabilities.

Going back to the PT COUNTS study, we know that the students included are not yet involved in transition planning (which typically starts around age 14). But, should we wait until they are 14 to start working on self-care skills? We all know from our discussion of motor learning principles that frequency of practice is important. So starting early (i.e., now) means students will have a lot more time to practice and learn from their failures and successes.

Now that we confirmed the importance of self-care skills, let’s look at the possible reasons why only 5% of primary goals are self-care goals.

- Perhaps, self-care goals are additional, but not necessarily primary goals?

- However, a quick count of the total number of all goals (primary or otherwise) show that only 10% of all the goals deal with self-care. Still a very low number.

- May be self-care is not a concern?

- The Pre-test SFA criterion scores of the students shown on Table 2 of the Effgen et al (2016) article shows that performance for the categories of Eating and Drinking, Hygiene and Clothing Management are at similarly low levels as the mobility categories. So, these self-care categories may be just as concerning as mobility.

- A reason pointed out by the authors is that may be another IEP team member is addressing self-care goals?

- Comparing Pre- and Post-test SFA criterion scores showed that the categories of Eating and Drinking, Hygiene and Clothing Management recorded the 3 lowest rates of positive change: only 37-39% of the participants. So was somebody else really addressing self-care? And was it being addressed adequately?

Here are some recommendations to increase focus on self-care:

- Why not make posture and mobility goals more functional by using self-care activities as meaningful outcomes/IEP goals. For example:

- Johnny will wash and dry his hands independently in the bathroom sink 3x during the day.

- Mary will independently walk 10 feet to her cubby using her posterior walker, retrieve her coat and put it on at a similar pace as her peers prior to recess and dismissal every day.

- See the posture and mobility components here?

- The same goes for OTs and Speech language pathologists: can self-care goals be incorporated into the student’s IEP goals?

- Finally, OTs, PTs and Speech language pathologists should collaborate with the IEP team to ensure that self-care skills are being addressed adequately, if not by them, then by somebody else.

SheFreak says: I am so glad you brought this up! I saw the excellent discussion but after reading your comments, I realize I need a more impassioned reaction!! Self-care is critical for many outcomes, especially participation. I love your recommendation for weaving 2 or 3 needs into one goal. This is an important area that often requires attention from many different approaches and disciplines. For this reason, it may have fallen between disciplines. PTs can and should be working on self-care.

HeFreak’s 3rd Takeaway: School-based PTs are integrating into school activities!

Another win! For 61% of the students, performance of primary goal behavior was addressed and measured within a school activity or routine. Per goal category, this number is 94% for self-care goals. This gives us another reason to promote the use of self-care goals – they encourage more participation during an actual class routine.

On the other end of the spectrum, the percentage of integration is lowest for recreation/fitness goals (just 47%). It can be argued that this somewhat corresponds to the high percentages of acquisition and fluency level goals for recreation and fitness at 76% and 85%, respectively. Meanwhile, generalization level goals were none existent (0%).

Possible reasons may include:

- Scheduling issues (as mentioned by the authors) – i.e., therapist’s schedule does not correspond with student’s PE class or recess

- Lack of recess time/space or PE classes

Whatever the reason, I still think we can do a better job of measuring and addressing recreation goals during PE class or recess for a variety of reasons:

- By integrating into the class routine, the student’s recreation/fitness goal is not just a PT goal, but a goal embraced and addressed by all school staff, including PE teachers and recess aides. This increases the practice frequency.

- Generalizing recreational/fitness skills require variability as discussed in Motoropoly. What better way to introduce real-world variability than playing with other students with different skill levels.

- Integration promotes participation. Why measure student’s performance playing with a PT, when student’s participation in play with other students can be measured instead?

SheFreak says: We both came away with this, great minds think alike, HA! But, I do love your logistical approach! Perhaps some PTs are shying away from PE class because they are afraid s/he will be asked to take it over!! Too close to be funny? In any case, I do feel that PE class and recess are excellent times for PT intervention and collaboration. Don’t forget to use the Essential Documentation Tools for OTs, PTs & SLPs, there may be some ideas or ways to be more deliberate with our clinical reasoning and using data to make some of these service delivery decisions.

HeFreak’s 4th Takeaway: PTs are generally good at prognosticating 1 year goals.

That student’s goals were generally achieved means that PTs are good at creating realistic goals for the year. Chiarello, et al (2016) actually agrees with this in their discussion.

This is another great news since prognosis is an important element of PT practice (APTA, 2014). This finding offers more relief than the findings of Johnson & Long (2010) that only 48% of pediatric therapists surveyed used prognosis to set goals. The prognostication accuracy in this study may be due to the increasing number of research published in the field of rehabilitation. A less positive view is that the goal attainment may have been a Hawthorne effect, where PTs participating in the research may have worked harder to achieve the goals they have set knowing that they are part of a study.

Where can we improve on prognostication?

- Chiarello, et al (2016) pointed out that PTs in this study “may have underestimated the progress that younger students could make” since goals were generally exceeded for students 5-7 years old. We should reflect whether we need to adjust our goals up for younger students.

- How are we doing with longer term prognostication? It is surely difficult, but it is necessary to achieve our role as related service providers in preparing “them for further education, employment, and independent living” (Public Law 108–446). Perhaps, important transition skills such as self-care (as discussed above) would come to the forefront if we look at the student’s lifespan goals.

- Collaborate with the school team, parent and child to set long-term expectations and predict where the student will be at the time of graduation from school. Think about:

- Post-secondary school

- Employment

- Community participation

- Independent living

- Take this long-term prognosis when creating the student’s annual goals. Is there a skill that the child needs to learn now that would be a building block to achieve their very long term goals?

- Collaborate with the school team, parent and child to set long-term expectations and predict where the student will be at the time of graduation from school. Think about:

SheFreak says: Hmmm when is the last time I prognosticated? It HAS been a while! This is an important clinical contribution school-based therapists need to provide IEP teams. This long term perspective can really light a fire under us to accelerate student progress. Will this preschooler (who will likely be over 6’ and >200#) be able to achieve a stand-pivot transfer in middle or high school if I do not get him bearing weight on his feet NOW? It is difficult to maintain perspective with consistent input. If you only practice in the preschool, how about visiting the high school class your student may go to? When is the last time you watched a typically developing 11-year old at recess? We need to get and keep a big picture perspective so our goals are on point!

HeFreak’s 5th Takeaway: Younger students progressed more than older students.

Chiarello, et al (2016) found that “students 5 to 7 years of age had higher goal attainment than students 8 to 12 years of age for their primary goals.” Note that the authors added that the older students (8-12 years old) still achieved their expected goals, but they did not exceed them, like the younger students did. What the study did not clarify was the type of interventions received by either age group. Did they receive similar interventions?

Some things to think about:

- Reflect on the goals and interventions you use for younger and older students.

- Are your goals age-appropriate and are they relevant to the student’s school expectations?

- Do you use the appropriate amount of remediation and compensation? Older students who have less potential for intrinsic change may need more compensation to succeed.

- Do you consider critical periods of acquisition or developmental readiness for change when determining which goals to address?

- In the SF article, Child-focused vs. Context-focused Interventions {LINK}, we discussed that one way to identify the right goals is by identifying motor skills that the child is initiating, trying to modify or showing an interest in performing, but is having difficulty accomplishing (Darrah et al, 2011).

- This may also relate to activities that are typically included in their current school routine. There is a greater chance that a student will learn a skill, if there are more opportunities to repeatedly practice that skill in class (recall concepts of frequency and task specificity).

- Do you consider multiple episodes of care that are in line with critical periods of acquisition or developmental readiness for change? The student can take a break from services (i.e., an episode of care) when goals are achieved and/or when progress slows. A new episode of care can be started at a later time when the student displays readiness or reaches a critical period for acquisition. Sauve and Bartlett (2010) describes the benefits for such an approach.

SheFreak says: I am really concerned at some pervasive opinions I have heard, like: “We really intervene in the early years and try to move to consultation by 3rd grade or elementary school.” Age is just a number, people! Seriously, while age may be a consideration, this is a disturbing approach. School-based therapists should be looking for opportunities when our expertise can improve student performance or participation. We have A LOT of work to do in middle school transitions, during and following growth spurts, assessing work environments, work hardening, community exploration for engagement and other transition efforts. I, personally, witnessed a high school teacher convince our whole IEP team that a young man (15 years old) could be potty trained…and It. Happened. What a profound impact that had on his whole life! I think we have become convinced that consultation is the best way to make change, we have spent so much time and effort convincing others!! In some cases, consultation is best. But it should not be the norm. We need to apply deliberate, compelling clinical reasoning along with student performance data to our service delivery recommendations. I like the questions HeFreak poses above. We should challenge our own thinking and use peer reviews to get professional perspective. Check out the Midwest Spotlight on Andy Ruff to find the folks who changed his practice with his/her research contributions and direct experience.

~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~

To wrap up our 1st SheFreak Says, HeFreak Says article, here are our:

Top 5 lessons for school-based OTs, PTs, and SLPs

- Create more generalization goals.

- Think ahead and challenge your team to picture the student’s life as an adult.

- Establish more self-care goals with the IEP team.

- Look for opportunities to integrate interventions into the school routine.

- When using tests, read the accompanying manual or research articles.

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

Join our discussion below, on Facebook or on Twitter.

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

Readers of this article also read:

IEP 4.0 – Developing Data-based and Student Focused Goals

Motoropoly 2: Motor Learning Principles in School – Task Specificity, Difficulty & Variability

Recognizing ICF Domain Words…Amusing Musings

Article Review: Child-focused vs. Context-focused Intervention

October 28, 2016 at 4:34 pm

Great review!! I liked the points on self care and generalization for goals. I question if team collaboration is occurring enough to support collaborative goal writing and shared implementation of student supports and intervention on goal areas? I think it varies based on therapist contracts, school teaming of special and regular education teams,/system and data collection systems established in varied schools. Are therapists using excel spread sheets to track data or a specific data system? Isis?

November 2, 2016 at 7:08 pm

My own experience and conversations with therapists all over the country confirms your suspicion that there is a big variety. You make a good point about the importance of collaborative goal writing. It makes sense that more shared implementation would occur if the whole IEP team came up with the goals together.

In fact, when I was reading the PT COUNTS articles, I was wondering whether the goals were written collaboratively with the team. I’m sure we’ll hear more from the PT COUNTS researchers who are planning to publish more articles.

Personally, I’ve created graphs to monitor a student’s progress. And I allow the students to enter the data, and then I ask them what they think it means. Excel is a great way to do this – it can easily graph the student’s progress.