[smbtoolbar]

Written by Laurie Ray, MPT, PhD, who has over 18 years of experience in school-based practice and is a state-level PT consultant for public schools. She also consults for Medicaid and Adapted Physical Education for her state and is an Associate Professor at UNC-Chapel Hill. Laurie also teaches continuing education via Apply EBP. More about these courses after the article below.

With Bonus: Physical Activity Evidence/Resources

Physical activity is critically important to children, and clearly public schools. We are making progress in decelerating the obesity epidemic with our children, according to the Centers for Disease Control. However, “the current reality is that 32 percent of children and adolescents (ages 2-19) are overweight or obese, and most are too sedentary, do not meet physical activity recommendations, and are not offered sufficient physical education.” (SHAPE America, 2016).

National recommendations call for 60 minutes of physical activity DAILY for school aged children (see SeekFreaks’ Physical Activity Guide for Educators). One of the primary ways we improve physical activity in American public schools is physical education classes. Although, few schools commit 60 minutes each week, let alone 60 minutes each day for structured physical activity.

Physical education and physical activity standards and assessments vary widely from state to state and district to district; even in each school as the principal most often determines the amount of PE will be provided. Also, professional requirements for PE teachers or what qualifies as ‘physical education’ is wildly variant. Only 10 states prohibit withholding physical activity as punishment and 13 states prohibit using physical activity as punishment!!

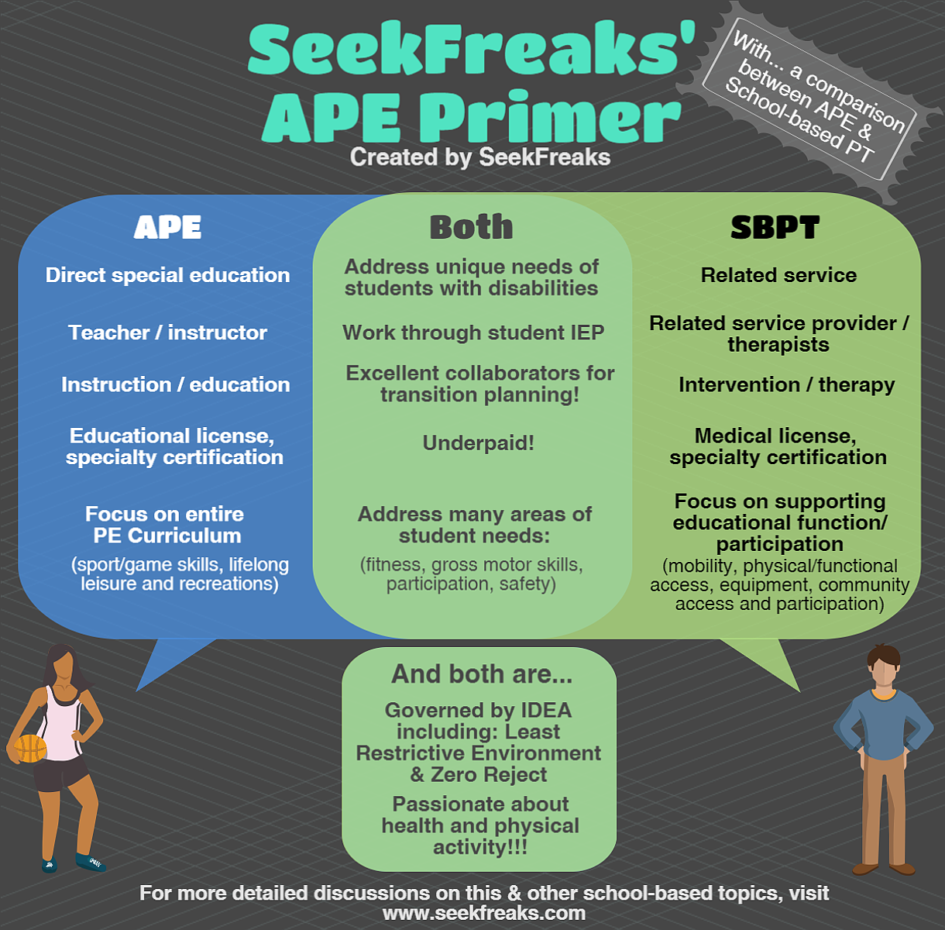

Students with disabilities often receive adapted physical education as a part of her/his Individualized Health Program (IEP). But the variability of standards, qualifications, expectations and implementation for APE is even more erratic. I think because ‘physical’ is in both our titles, physical therapists are often substituted for certified or qualified APE teachers.

But this does not mean our colleagues in occupational therapy escape the reach of IEP teams who want him/her to “just write up a few APE goals…would you?” It is very important that we establish and consistently enforce clarity in the boundaries between our practice areas (not only for APE and PT but also OT and PT, but that is another post to write!!). IEP teams often do not understand why a PT or OT who is a ‘motor’ expert cannot draft APE goals for the student. We should take this on as an opportunity for education…There are several important distinctions.

The most direct way to answer this request is to explain that:

- OTs and PTs are healthcare professionals, not educated in or competent with PE standards

- PE is a curriculum, called by many names in each state, usually with Health or Healthy in the title

- As a curriculum, there are educators (not therapists) licensed (and in best practice, certified) in this curricular area who must be the person the IEP team works with to evaluate the student’s need in this area (while this can and should be collaborated on with relevant related services providers!)

- Drafting student goals and monitoring student progress should be done by an educator or instructional staff in the PE class (again, important to collaborate with all relevant IEP team members, especially related service providers!)

- APE is not a related service in any way; it is a direct educational service= specially designed instruction in the area of physical education

A very helpful strategy I have employed to convey the difference between related services and adapted physical education is to provide a simile with another curricular area:

- Them: What is the assessment tool that should be used for determining eligibility for APE?

- You: What is the assessment tool that you use for determining need for specially designed instruction in English Language Arts?

- Them: That depends on what the area of need is.

- You: Right, same with APE. Is the area of need fitness/endurance, strength, gross motor skill, behavior, attention, game skills, motor patterns…This is why a PE teacher needs to select an appropriate assessment based on the referral concerns.

- Them: How do we/IEP team know if this student requires APE?

- You: How do you determine that for specially designed instruction in English Language Arts?

- Them: We discuss if her/his needs can be met with modifications or if we have to change the curriculum completely…oh, is it the same for APE?

- You: Yep.

- Them: But, how do we draft APE goals/determine how to monitor student progress?

- You: How do you draft student goals/decide on progress monitoring for English Language Arts?

- Them: We need someone who knows the curriculum and the student’s present level of academics/function to draft it for our discussion.

- You: Same for APE.

- Them: But can’t you do it? You know motor development and motor skills.

- You: Thank you for your confidence in me, but that would be like asking a literacy teacher to draft a math goal for word problems. We just don’t know the curriculum! It takes someone in the class to monitor progress and who is knowledgeable about grade level expectations in PE.

= Adapted physical education is to physical education what special education is to general education.

There are many areas addressed by adapted physical education and physical therapy that do overlap; however, our professionals are not interchangeable! School-based physical therapists should not provide physical education (adapted or for general education) evaluation or instruction unless s/he have the valid teaching credential for that state.

APE is instruction in the physical education curriculum; whereas, physical therapy provides interventions within our scope of practice. It is VERY appropriate and often essential that our professions collaborate together to promote motor function and lifelong physical activity.

The adapted physical education class is an excellent location for delivering OT, PT…any related service, especially speech/language services (⇑ moving = ⇑ talking)! Many classes with only students with disabilities benefit from special projects and activities provided collaboratively by APE and PT as well as other professionals (e.g. preparation for field trips, student-led IEPs, community outings, student-run enterprises).

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

Here’s the Bonus!!

As health care professionals, we are all concerned about our children and physical activity. There is an ample evidence base for the positive impact of physical activity for almost anything with a body (e.g. children, elders, humans of all kind and all types of animals)! We know movement is good and improves learning.

Here are some references and resources that would be helpful to share with many of our collaborators, especially students, instructional staff, parents and administrators in public schools. May I STRONGLY recommend you read or at least skim these first 2 references offered (CDC, 2010 & US EoD, 2011)? They are awesome and persuasive!!

Evidence

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010).The association between school-based physical activity, including physical education, and academic performance. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Or SeekFreaks’ review of this article: Physical Activity Improves Academic Performance

- S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education Programs, Creating Equal Opportunities for Children and Youth with Disabilities to Participate in Physical Education and Extracurricular Athletics, Washington, D.C., 2011.

- Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/wscc/index.htm

- SHAPE America – Society of Health and Physical Educators (2016) http://shapeamerica.org/shapeofthenation

- Protect PE http://VoicesforHealthyKids.org/PE

- Empower all students through effective health and PE programs http://shapeamerica.org/50millionstrong

- Behrman, A. (2015) Keynote presentation: APTA Section on Pediatrics Annual Conference 2015. Pittsburgh, PA.

- Bluechardt MH, Wiener J, Shephard RJ. Exercise programmes in the treatment of children with learning disabilities. Sports Medicine 1995;19(1):55–72.

- Dwyer T, Blizzard L, Dean K. Physical activity and performance in children. Nutrition Reviews 1996;54 (4 Pt 2):S27–S31.

- Howland, D., Trimble, S. & Behrman, A. (2014). Neurological Recovery and Restorative Rehabilitation, Chapter 28, pp. 299-410; Mac Keith Press: UK.

- Jarrett OS, Maxwell DM, Dickerson C, Hoge P, Davies G, Yetley A. Impact of recess on classroom behavior: Group effects and individual differences. Journal of Educational Research 1998;92(2):121–126.

- Lobo, M. A., Harbourne, R. T., Dusing, S. C., & McCoy, S. W. (2013). Grounding early intervention: physical therapy cannot just be about motor skills anymore. Physical therapy, 93(1),

- Ma, J. K., Mare, L. L., & Gurd, B. J. (2014). Classroom-based high-intensity interval activity improves off-task behaviour in primary school students. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 39(12), 1332-1337.

- Mahar MT, Murphy SK, Rowe DA, Golden J, Shields AT, Raedeke TD. Effects of a classroom-based program on physical activity and on-task behavior. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2006;38(12):2086–2094.

- Pellegrini AD, Davis PD. Relations between children’s playground and classroom behaviour. British Journal of Educational Psychology 1993;63(1):88–95.

- Ratey, J. J., & Hagerman, E. (2008). Spark: The revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain. Little Brown & Company.

- Salamone, J. D., Correa, M., Farrar, A. M., Nunes, E. J., & Pardo, M. (2009). Dopamine, behavioral economics, and effort. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience.

- Scholey, A. B., Moss, M. C., Neave, N., & Wesnes, K. (1999). Cognitive performance, hyperoxia, and heart rate following oxygen administration in healthy young adults. Physiology & Behavior, 67(5), 783-789.

- Shephard, R. J. (1997). Curricular physical activity and academic performance. Pediatric exercise science, 9(2), 113-126.

- Sibley, B. A., & Etnier, J. L. (2002). The Effects of Physical Activity on Cognition in Children. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 34(5).

- Sisson, S. B., Broyles, S. T., Baker, B. L., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2010). Screen time, physical activity, and overweight in US youth: National Survey of Children’s Health 2003. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(3), 309-311.

- Stewart JA, Dennison DA, Kohl HW, Doyle AJ. Exercise level and energy expenditure in the TAKE 10! in-class physical activity program. Journal of School Health 2004;74(10):397–400.

- Taras, H. (2005). Physical activity and student performance at school. Journal of school health, 75(6), 214-218.

- Tuckman BW, Hinkle JS. An experimental study of the physical and psychological effects of aerobic exercise on schoolchildren. Health Psychology 1986;5(3):197–207.

- Verret, C., Guay, M. C., Berthiaume, C., Gardiner, P., & Béliveau, L. (2012). A physical activity program improves behavior and cognitive functions in children with ADHD: an exploratory study. Journal of attention disorders, 16(1), 71-80.

- Williamson, D., Dewey, A., & Steinberg, H. (2001). Mood change through physical exercise in nine-to ten-year-old children. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 93(1), 311-316.

- Wrotniak, B. H., Epstein, L. H., Dorn, J. M., Jones, K. E., & Kondilis, V. A. (2006). The relationship between motor proficiency and physical activity in children. Pediatrics, 118(6), e1758-e1765.

Web Resources

- SeekFreaks’ 2 Tools to Promote Movement in the Classroom

- Minute to Win It games for breaks and indoor recess

- Good educational music by Jack Hartmann-integrates movement with academic themes and catchy tunes

- Active Child Research

- NC Energizers

- Wendy Suzuki – Exercise and the Brain TED Talk

- Beyonce Let’s Move

- Just Dance

~~~~~~~~~~ 0 ~~~~~~~~~~

Readers of this article also read:

Catch the author, Laurie Ray in her Apply EBP webinars